With its rhythmic striking system that hits at different heights, Street Fighter‘s combat system was expanded to become a branching, freestyle duet in SFII, sung by the sound effects and character voice samples. After Street Fighter Alpha’s swappable systems pushed the series’ fighting game formula to it’s limits, Capcom streamlined its base mechanics and meter functions for Street Fighter III, using the CPS-3’s CD format for gritty, stylized art on detailed stages against a funky soundtrack. Street Fighter III: New Generation’s refined mechanics maxed its beats per minute and rewarded improvisation, turning it into a fluid hip-hop fighting game.

Street Fighter’s controller is comprised of two instruments: a striking six button keyboard and a scratchable joystick turntable that winds the character forwards and back. Street Fighter’s every normal strike is a note with a pitch between quick and sharp and slow and blunt, sustained by negative edge, linked in natural progressions, and accentuated by chorded special moves, creating melodies set against the stage’s background music. The ticket to Street Fighter’s striking symphony is earned with timing, synchronicity, and harmony, and, starting with Super Turbo, crescendos with a high-damage Super combo that can knock out an opponent to an explosion of color and sound.

As action game characters are collections of movements with sound effects, they are essentially person-shaped instruments with different kinds of notes. In SFII, that means meaty notes when striking, muted when blocking, and high pitched when taking damage. SFIII’s Target combos replaced Alpha’s freeform chain combos that allowed a succession of kicks and punches to be canceled by higher intensity normals, instead giving every character more than a dozen predefined strike patterns of complementary moves like musical scales to be memorized and build upon.

A player’s style, be it aggressive, frantic, defensive, calm, deliberate, or whatever, is imbued with a natural tempo. If Capcom’s fighting game formula creates a melodic rhythm in the back and forth, then its harmony depends on the player’s ability to properly tune their playstyle to their instrument. Alpha 3’s swappable Ism system that could slot a character with Super Turbo’s, Alpha’s, or Alpha 2’s rulesets was an attempt to flex the natures as much as possible, essentially able to turn a guitar into a harp or a violin because they all have strings. Street Fighter III corrected this complexity, adding more tools to the core mechanics so characters could hit more notes every moment as the stage music sets the rhythm. Learning to play with intention is the difference between making noise and building a tune.

Negative edge has long been fundamental to Street Fighter‘s design, where a button consists of a down press and a release, so a strike press runs the animation, the joystick inputs the instructions for a special move, and the button release executes that special. The series’ musicality is accentuated by the advanced input swapping- pressing and holding a normal button while a completely different animation is playing makes the second button the new active input, and so it can easily transition any normal into any special of a different intensity or outright change strike types. If every button is a musical note, these chords have a tight window to be struck, requiring a tatap rhythm on your combat keyboard that beautifully sustains Street Fighter’s beatboxing symphony.

New Generation’s big innovation was its awesome parry mechanic, a complement to blocking that blurs the line between offense and defense. By pressing towards a mid/high attack and down at a low attack the moment before it connects, the player deflects the hit to a satisfying clashing sound, negating damage and blockstun to create an opening to hit back before the attacker recovers. Since every blow could be parried, it was beneficial for players to learn all the characters so they can anticipate what moves would be used against them. Because players can parry in mid jump, air blocking could be removed all together which brought the gameplay closer in line with Street Fighter II without being limiting. The parry keeps gameplay on the ground for close quarters fighting, keeping the pressure high without reaching hyper fighter speeds.

Mapping the parry mechanic to an always available button exemplifies SFIII’s desire to maximize technique, but the goal affects everything from throws to character mobility. By executing throws with Low Punch and Low Kick rather than pressing a direction and a normal, they become more reliable to execute than combining a directional input and a strike, which was more likely to cause errors in the heat of battle when a player is pressuring a character up close with normals. Similarly, the new dashes forwards and back made matches faster by letting players quickly change the distance between combatants. Dashing drastically changes your ability to approach and is a phenomenal way to add or relieve pressure. When added to combo strings, dashing can provide follow up after knockback or chase down launched enemies to perform juggles, which lengthened combo strings and raised Street Fighter’s already high skill-ceiling.

Street Fighter III’s additions to the series’ every aspect adds up to significantly different matches than before. Since players can charge their opponents quickly and deflect attacks, the gameplay can create momentum that dynamically flows between players. This energy pairs well with character details such as moves that blow clothes back, which adds to the sense of weight and consequence. The characters themselves have expressive personalities thanks to their additional animations. Because of this matured design, Street Fighter III’s fights are strong, physical duels between well-defined characters and set against an energetic soundtrack, the fidelity of which simply could not be equaled by 3D polygonal games of the time.

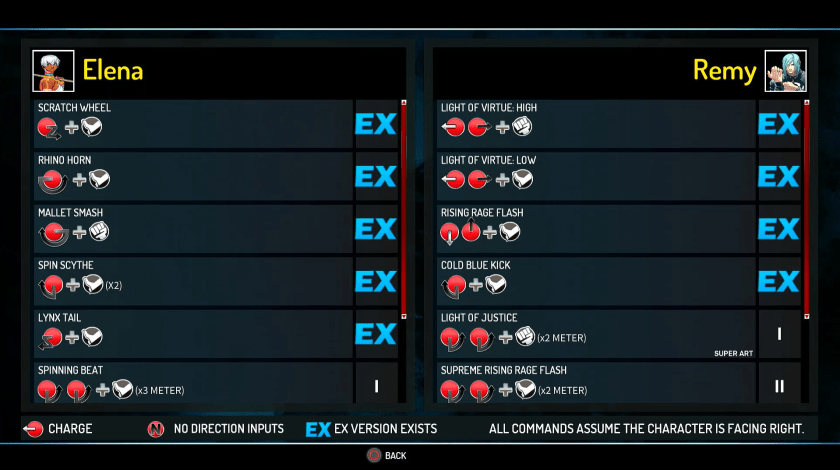

As its predecessors had, iterations changed SFIII into its own subseries that added new characters and modified movesets, but together added new offensive and defensive options. With 2nd Impact, SFIII implemented meter costing EX Specials, enhanced fourth versions of every special that often have invincibility frames or low startup frames and added properties. It also brought meter consuming tech throws provide a tossed player a smooth landing, and taunts gave the ability to tease the person that tried throwing you. 3rd Strike added guard parries, available during block stun, giving more time to interrupt an opponent’s combo patterns. Parrying allows any fighter to take over the duet, letting their fists beat out their solo.

SFIII reworks Alpha’s system heavy design heavy, adapting ideas into mechanics like the parry system or into background calculations, as with the character health and damage scaling. While counter attacks in Alpha did more damage than regular attacks, SFIII’s combo heavy gameplay would end matches too quickly and let veteran players dominate new challengers if left unchecked, so each successive attack in a combo are given damage reductions to balance it all out. The combat is gorgeously sophisticated and simple.

With these new mechanics and systems, precision becomes that much more important. Executing Target Combos, nailing your parries, and dashing to juggle an enemy is all about control and timing, and when two fighters are hitting their BPM, the game dramatically ramps up its speed. This is especially true with the advanced timing of 3rd Strike’s Red Parry mechanic, which is activated during blockstun rather than right when getting attacked. Red Parries counter combos and end the branching guessing game of blocking successive attacks that comes with SF’s classic branching exchanges.

In skilled hands, Street Fighter III’s rhythmic striking system can mix a music video of offense and defense on every stage, and fighting the fire and ice shooting Gill proves the beautiful music that battling DJs can spin. I’ve whittled down his life a little more than he mine, and go in for the last combo. Dashing him down, I jump when he raises his hands to fire a ball, and fly towards the diagonal shot he faked me on. I recover quickly and charge again only to head straight towards a medium punch, but I bat it away and take the advantage to jab him in the face, smack him with a cross, and fierce into my EX special to lay him out. But then his Super Art executes and he is resurrected with a full health bar and he stands before me unfazed by my exhaustion. That’s a lesson on establishing a quicker tempo, balancing beats and rests, and taking control of the energy flowing between players.

By the late 1990’s, players were transitioning to home machines with 3D graphics and long, story-driven campaigns, marking an end to arcades and Street Fighter’s dominance. While Capcom’s premier fighting game evolved a satisfying and complex combat system, it required high technical ability from an increasingly small market wooed by the flashy style of Hyper Fighters like X:Men vs Street Fighter and the visual allure of polygonal fighters such as Soul Calibur. As Street Fighter’s sprite era closed, it solidified mechanics and streamlined systems into its fighting game formula, fast and fluid, and would be ready for the day the world stepped back into the ring. Because while the song may change, the Martial Artist remains.

DEVELOPER: Capcom

PLATFORM: Capcom Play System 3

1997

Dane Thomsen is the author of ZIGZAG, a sport-punk adventure in a world of electrifying mystery. With the voice of her people as her guide, Alex walks neon purple streets thrown into chaos, wielding the concussive force of her baseball bat the mighty ‘.357’ against the forces of evil. Print and kindle editions are available on Amazon. For sample chapters and to see his other works please check out his blog.