On my third infiltration into Ground Zeroes’ Camp Omega, I found an electrical panel that allowed me to cut the power to the surrounding facility, disabling all the lights and the several security cameras so I could quietly rescue the prisoner at its belly. It was the latest in dozens of exploitable gameplay options built into Omega that proved it was a dynamic, multi-faceted place that enabled and rewarded a variety of playstyles. The first game powered by the Fox Engine, GZ introduces players to the new levels of agency offered in the second part of the Metal Gear Solid V saga, The Phantom Pain; ideas that evolve the classic Metal Gear design.

Ground Zeroes continues days after the events of its immediate predecessor Peace Walker. By the end of that story, Big Boss (aka Naked Snake (aka David Hayter)) together with Kazuhiro Miller had assembled a private military company at their offshore Mother Base and come into possession of his very own Metal Gear.

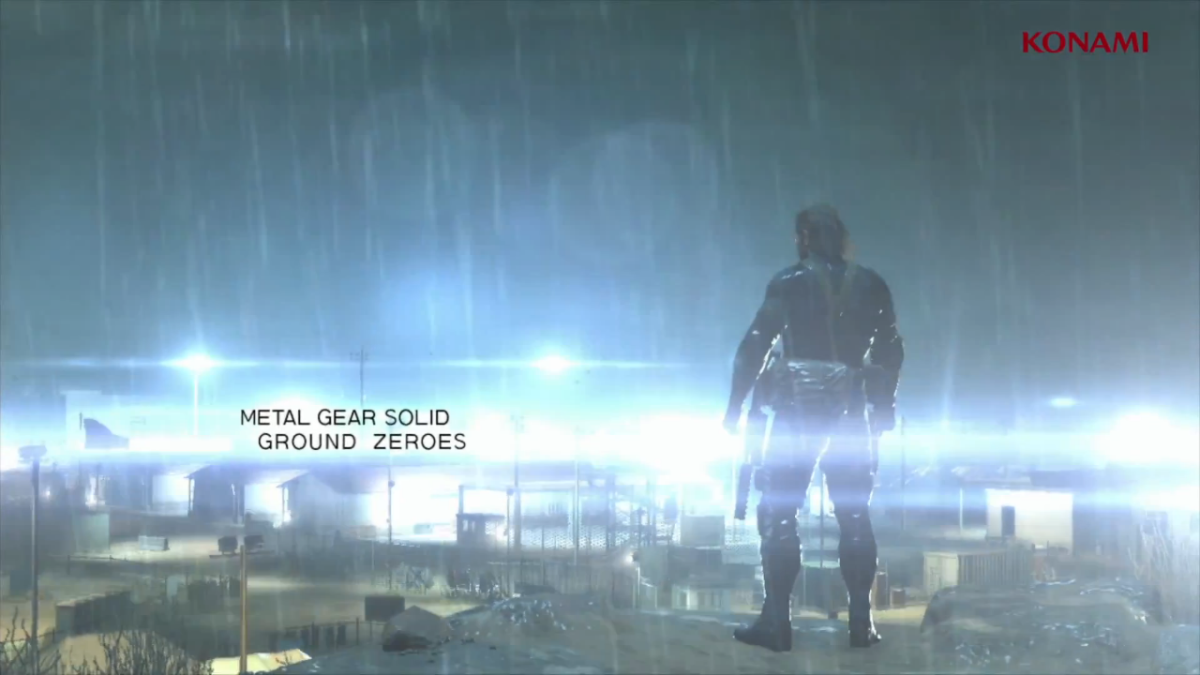

16 March 1975. Torrential rain strikes the sign outside the prison base. A trench-coated man walks through occupied cells of the detention section. He stops at a cage and tosses a Walkman ™ to the small blonde boy shivering inside. Those who’ve played Peace Walker will recognize Chico, member of the Cuban Sandonista army Snake had allied with. The man identified as Skull Face then takes a jeep to a waiting helicopter, removes all identifying marks from it and his squad of soldiers and climbs aboard his ‘Trojan Horse’. The scene contains VO between Kaz and Naked Snake (aka John (aka Keifer Sutherland)) telling us that Peace Walker’s pacifist-turned-spy Paz is also being held hostage and our Hero has to get her back before she reveals the secrets of his Militaires Sans Frontiers. They reason there’s a connection between Paz’s detainment and an upcoming UN inspection. Snake appears climbing up the cliff side outside the base, entering Omega as the departing choppers pass overhead.

The first real evidence of Ground Zeroes changing design is found in this sequence: it’s one long take. Before this, Metal Gear’s legendarily long cinematics were comprised of half a dozen scenes each, bouncing from real time in-engine graphics to illustrative graphs to live action historical footage to talking-head Codec exchanges and more. Unfortunately here, the VO isn’t grounded enough to establish a timeframe, leaving you to assume that parts of the conversation are referring to events that will transpire at some point down the line.

While the CODEC device has been mercifully retired, its practical application has been smartly reworked. Rather than dialing up support through a menu only to be accosted by a long-winded explanation about Lord-Knows-What framed as a treatise on Godzilla as a metaphor for digital societies being given status as Life in the eyes of The Law, juicy camp deets and objective reminders are a quick L1 pull away. It’s so easy it must have been a mistake (oh God, it’ll be an L1 activated rolodex in TPP). On one hand, the constant companionship breaks the feeling of isolation; on the other, it maintains a sense of time and flow. For what it’s worth, I’ll take the latter.

While the CODEC device has been mercifully retired, its practical application has been smartly reworked. Rather than dialing up support through a menu only to be accosted by a long-winded explanation about Lord-Knows-What framed as a treatise on Godzilla as a metaphor for digital societies being given status as Life in the eyes of The Law, juicy camp deets and objective reminders are a quick L1 pull away. It’s so easy it must have been a mistake (oh God, it’ll be an L1 activated rolodex in TPP). On one hand, the constant companionship breaks the feeling of isolation; on the other, it maintains a sense of time and flow. For what it’s worth, I’ll take the latter.

Since MGS3, the Metal Gear progression has consisted of a linear path of small densely packed maps with a single entry and an exit. Because of that linearity, gameplay options had relied on an ever increasing backpack of items. Ground Zeroes sandbox radically improves the ideas from MGS2’s Big Shell, giving you flexibility in your preferred direction of attack. Reducing Snake’s arsenal met it from the other side, streamlining the mechanical burden to a few key moves that easily take advantage of those options organically built into the environment. The two elements are better able to complement each other.

The tighter design retains the traditional Metal Gear experience- including adapting old frustrations and creating new ones. Even with the changes, it’s all too easy to get spotted and not understand why. The new indicators are informative but not nearly as informative as you need, especially for guards range of sight, so the majority of the lessons you’ll learn still come from trial and error rather than applying practical skills. The new reflex slow-mo is problematic if you’re spotted at the edge of a piece of cover you’re running for, making you try to sluggishly maneuver out from behind the obstruction to get your shot in before your presence is radioed in. Even the new checkpoint system feels arbitrary, resetting you to places you hadn’t been and conditions that weren’t that way even if you had. The many facets of the Snake/Enemy feedback loop still don’t cohere satisfyingly.

Metal Gear desperately needs a stop and pop cover system. Sons of Liberty kinda had one and definitely had a better wall cling, it just needed a button like in Guns of the Patriots (that that game’s responsible for taking out the jump out shot is just one more strike against it). If there were better options to utilize and transition between cover here, things would interlock better- you’d be better equipped to survey your surroundings and traverse the environment. Uncharted had better sneaking without working so hard for it and that’s not even the point of that franchise.

You’ll probably find Chico in the old prison first. When you do, you’ll probably be surprised that he fights back and has to be choked and assume he’d been brainwashed during his obvious torture. Carry him to the closest evac point and you can call in your own chopper. Some thirty seconds later, Morpho will descend and whisk the boy away, leaving behind his Walkman and the first of his many tapes.

Metal Gear Solid V’s new open-world trappings put it in an awkward place. Tasked with finding these two prisoners and without any friendly NPC’s to route you, it’s hard to direct the player to their objective. Chico’s first tape is meant to offer a helping hand. Utilizing Kojima’s penchant for requiring lateral thinking, the tape provides distinct audio cues meant to drive the player in the right direction. But because he couldn’t rely on the player finding the source of those cues, other devices were implemented to help get them there, including a truck near the first evac point that’ll take Snake directly to the facility that houses Paz. If for some reason you missed that- guilty!- you can deduce her location by the thick swarm of guards outside it. Spend enough time searching and you’ll get there eventually.

That’s Ground Zeroes mission: two phases repeated twice: infiltration and extraction. Go out. Come back. Do it again. Why? Peace Walker. It’s one of the weakest, calmest narrative sequences I think I’ve ever seen in my entire life, made limper by the ill-defined connection between the immediate plot and the cinematic that opened the game. Deep, complex gameplay can’t make up for a lack of momentum. Executed directly with no attempts to collect Chico’s tapes, it’s hard to see how Skull Face was even important for the task at hand.

Snake returns to find Mother Base burning and his men dying. The narrative ends on a cliffhanger.

Ground Zeroes mission is ultimately lackluster, free of even a single instance of the series famously ingenious boss fights. That its end is supposed to be gut-wrenching, a moment that will establish the entire setup of The Phantom Pain and convince you to invest another 60$ on top of the 30 you paid for this, makes its flaccidity all the more confounding.

If you happen to be the type to pour over the mission briefings before starting a new game, you’ll be privy to the distress call that sent Snake after Chico and the nature of the UN inspection, key to the finale. If you didn’t, well, you’ll be given little in way of an explanation other than vague allusions that don’t sustain motive. The first Metal Gear Solid used the same technique on the PSX but to much greater success, as Campbell pointedly summed everything up within minutes of Snake’s arrival at Shadow Moses. Considering those details were relayed via Codec, maybe Kojima should have stayed with those talking heads.

Chico’s tapes bridge the gap between the opening and end. Yeah, it’s disappointing that the narrative relies so heavily on audio logs but at least they’re contextually relevant. The tapes reveal Skull Faces sadistic abuse on his two prisoners, twisting them, turning each on the other and on their home. It also has logical consistency within the larger narrative, explaining Chico’s resistance to Snake’s rescue. If nothing else, it’s an interesting narrative experiment that can be pieced together.

Chico’s tapes bridge the gap between the opening and end. Yeah, it’s disappointing that the narrative relies so heavily on audio logs but at least they’re contextually relevant. The tapes reveal Skull Faces sadistic abuse on his two prisoners, twisting them, turning each on the other and on their home. It also has logical consistency within the larger narrative, explaining Chico’s resistance to Snake’s rescue. If nothing else, it’s an interesting narrative experiment that can be pieced together.

But the onus is on the opening to provide the context we need, not on the player to go looking for it. That’s one of story-telling’s irredeemable sins: hiding information crucial to your plot outside of that plot’s narrative. Without an explicitly stated, immediately recognizable initiating force, you automatically handicap your audience’s potential investment, prohibiting the story from being as emotionally powerful as it could be.

Where Ground Zeroes story and scripting falls flat, its art direction remain strong. Long time series composer Harry Gregson-Williams provides a soundtrack that recalls 80’s sci-fi with subtle orchestration suitable to his work since Sons of Liberty and recalls a tone that would seem appropriate in either Mass Effect or John Carpenter’s The Thing. With the cinematics real time rendering, Camp Omega has been built with diverse colors and lighting, letting the environment itself frame the events within. That one orange light in Paz’s cell really drives home what the direction could be.

Beating GZ opens Side Ops, extra missions that have you tackling new objectives and going further to demonstrate the options the gameplay design affords. Setting aside the fictional inconsistency of proposing that Snake has infiltrated this same complex half a dozen times, the side missions should be integrated directly into the main mission to showcase the gameplay possibilities and flesh out the dynamics of the facility. They’re already being made voluntary, make them important.

Unfortunately, from top to bottom, the rewards for taking advantage of those options don’t come close to compensating the effort involved. You could interrogate every guard and claim every weapon cache or you could tranq the handful in your path and be on your way. You could clear the area of patrols and destroy the anti-air emplacement to call your chopper into the center of the base or you could just spend the minute and a half running to the coast and call it safely there. You really have to want to take advantage of your options; the fact that I didn’t find the electrical panel until my third playthrough is testament to the variety at its core, the way I stumbled accidentally onto it is sadly telling of its ability to inform.

So what is Ground Zeroes, exactly? It seems like it’s mostly a prologue, roughly equivalent to MGS2’s Tanker Chapter, but even that’s not entirely analogous since it acts as a direct continuation of Peace Walker. Yet it typifies what Metal Gear has always been: a super complicated franchise with a lot of depth and a lot of problems that asks for a lot of investment from its audience. It’s noble to try to smooth out the gameplay wrinkles that have long existed in the series but those choices manage to leave a large, iron-shaped burn on the fabric. As a game, as a story and as a taste of what The Phantom Pain will be, Ground Zeroes is disconnected from itself and leaves you feeling that something’s there, even when you can’t see it. It’s a lingering itch you can never scratch.

DEVELOPER: Kojima Productions

PLATFORMS: PS4, XBoxOne, PS3, XBox360

2014

MGSV: The Phantom Itch