A Biohazard Outbreak

When Special Tactics And Rescue Squad’s Bravo team goes dark in Raccoon City’s Arklay Mountains while investigating grizzly murders, the Alpha team rescue party finds itself in a firefight against bloody claws and gnashing teeth, a scene Resident Evil brings to life with real actors dashing through the woods towards the safety of Spencer Mansion. Though primarily told through cinematic in-engine cutscenes framed by a static camera system, this live-action scene transitions the player into the B movie game’s world filled with zombies, mutated dogs, giant spiders, and, at the end, the perfect bioweapon, manufactured by the international conglomerate, Umbrella Inc. A controllable, branching B horror movie starring S.T.A.R.S.’ Chris Redfield or Jill Valentine and supporting characters, Resident Evil tests your delicious brain’s skills to survive a different kind of haunted house, discover the truth about a biological outbreak.

When Capcom’s prolific Famicom/NES dev Tokuro Fujiwara adapted the horror movie Sweet Home, about a film crew investigating a haunted house, into a game, its limited tech forced it to separate investigation and combat modes. Sweet Home’s scripted cutscenes emulated the original film, and the videogame industry would continue building these and other film techniques out over the 1990s as tech evolved. Sweet Home’s successor, directed by Fujiwara’s protégé Shinji Mikami with progression planned by newcomer Hideki Kamiya, would use PlayStation’s CD-quality multimedia and polygonal processor to adopt a design similar to Sweet Home’s but that came with an organically cinematic presentation. RE lives up to its film roots, in a classic setting.

The haunted house is a classic folklore location, stuck in our social psyche as a betrayal of the sanctity and safety of home, a place of secrets and twisted through trauma and despair, a soul corrupted to its rafters. Mysteries set here take the audience through old books, dusty rooms, and hidden passageways, all while death lurks in the shadows. Due to their single location and dark atmosphere, these stories are great for films on a budget, and, since they are dirty and decayed, are a great backdrop for Capcom to experiment making polygonal action games.

By 1996, Full Motion Videos had been used on PCs and for the small interactive film market that included Dragon’s Lair and Night Trap, where the game is a branching series of movie clips depending on what options are selected. The PlayStation’s multimedia capabilities let Resident Evil incorporate CGI and live-action scenes, with the now infamous cheesy acting and dialogue that both reflected the seriousness Hollywood took games at the time and strangely fit the niche genre of a niche medium. Because its camera system frames rooms stylishly to begin with, Resident Evil’s in-engine cutscenes need do little more than add letterbox bars during scripted scenes to differentiate gameplay and story, with the character models acting out scenes with simple animations. The scripting goes into the game progression, with a natural pacing that sequentially opens every door in the mansion until the exit.

Resident Evil also captures one of adventure game’s best characteristics: creating branching, open stories that react to your decisions. It’s first seen in the game’s two playable characters, each with own qualities and support. It has branching stories that can be handled in several ways, and its design is flexible enough to respond smartly to whichever you take. The game structure’s modularity was brilliantly used to make Chris’ early game very different than Jill’s, harder, lonelier, more resource intense; the closest thing the the game had to a difficulty select. It’s simply amazing. This design plus small randomized moments make replays slightly different, uniting the strengths of game and film in a way that was new and exciting for the time.

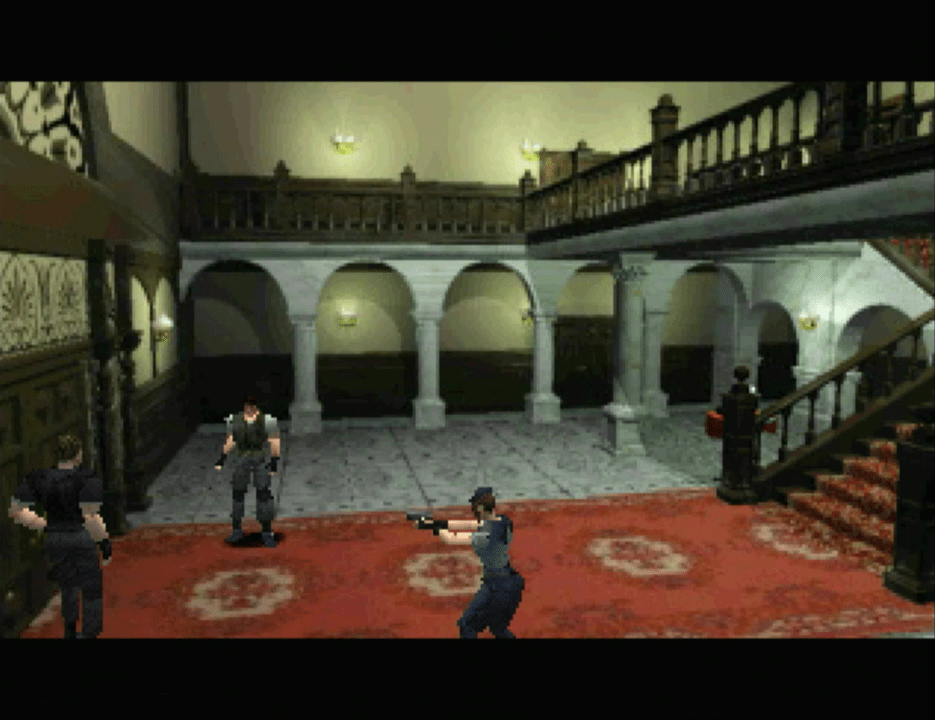

As reality sinks in for the remainder of S.T.A.R.S.’ Alpha team standing in the main hall, gunshots pop from the house’s west wing and you’re ordered to investigate, and are then automatically walked to one door in the room of several. Spencer Mansion’s mystery, coupled by atmospheric music, unnatural sound effects, and fully voiced scripted cutscenes would give personality to a place packed with cinematic moments, secrets, and monsters. With its conspiracy-fueled plot, Mikami and team designed a choose your own adventure B movie horror game filmed in the Spencer Mansion, haunted by science turned evil.

Evolving Perspectives on Survival Horror

Resident Evil is a 3D translation of adventure games, with a unified exploration and combat mode, an Inventory mode for using, equipping, managing, and investigating items, and a File mode for reading documents. Like other genres at the time, adventure games needed to think carefully about how to transition their ideas to polygonal environments, especially when those polygons were few and lo-res. This fidelity is important for a game that combines investigating an area that has finite resources with a combat system that relies on those resources. If a game is about finding objects, it should effect every aspect, so an adventure game with combat turns into a game about survival down to the usable ink ribbons required to save. To truly understand Resident Evil, it’s imperative to look at the three games that make up its genetic code.

The Legend of Zelda‘s action adventure has real-time events and assigns actions to buttons- in it, you control a character-shaped cursor named Link interacting with NPCs and objects by using items equipped to the NES’ A and B buttons. Zelda’s Hyrule Kingdom map is packed with interesting places to explore, and is divided into screens looking down on a section of terrain as you navigate, following paths to rooms with puzzle and combat challenges that reward you with items that sequentially open more room challenges. The exploration and action are the adventure, as you make the mysterious known with the sword in your hand and your wits.

1989’s Sweet Home is an amalgamation of adventure game elements inspired by genre classics, scaling Zelda’s Hyrule into a monster filled mansion with tightly directed progression, interrogation and interaction elements from Yuji Horii’s Portopia Serial Murder Case mystery, and layered with Wizardry’s party-based combat and item management. Sweet Home’s contribution was limiting items and controlling five uniquely useful characters who can die permanently, pushing the concept of scarcity and resource conservation. This creates an ever-shifting sense of strength and vulnerability, fear and relief, as items are consumed or discovered. The party gameplay prohibits it from Zelda’s real-time nature, but with its intimate, room-size scale, Sweet Home’s exploration is personal, making the items in your hand as tangible as the dread breathing down your neck.

Western adventure games have a rich tradition in Willian Crowther’s text-based Colossal Cave Adventure and On-Line Systems’ graphical adventure Mystery House, but the first game to translate to 3D was Infogrames’ 1992 Alone in the Dark, a mystery in the Derceto mansion inspired by Lovecraft’s Cthulhu mythos with two playable characters. Adventure games evolved how players interacted with the game world and AitD used different character states for actions such as push, search, and fight, modes set in the menu and engaged with the interact button. Though these separate modes successfully adapted adventure interactions into real-time gameplay, they ultimately keep game and player from truly connecting.

Dark’s Derceto houses all manner of puzzles, secrets, and monsters, and the polygons beautifully build its frame. Polygons are complex shapes that have flat texture sprites painted on their surfaces, and AitD’s characters and items are composed of different 3D shapes walking inside the mansion’s cube-shaped diorama that has simple 2D background wallpaper and is filled with different-sized cubes painted to look like desks and bookcases. AitD cleverly carries on the screen-based structure of graphical adventures that focuses on a single explorable subject by dividing its 3D maps into static camera angles looking at interesting points worth investigating, be it a fireplace or hallway with multiple doors. The number of angles per room depends on its function and size, but each had to communicate itself and its pathing. This objective static 3D model rendered more personal, information dense environments than the subjective rotational camera model Super Mario 64 revolutionized that same year. That the camera system implicitly creates paranoia that you’re being watched and elevates Sweet Home’s terror is a major plus.

Tank controls are the most logical choice to keep movement consistent across all camera angles, with left and right spinning the character, and up and down moving them forward or back in the direction they’re facing. Characters walk by default unless holding run and forward, which gives players small, precise movements to approach objects like that statue you need to push and large, fast movements for when you just need to book it. Fighting is activating your fists or weapon and using directions to turn your orientation or strike. This allows equipped weapons to be aimed before using, necessary for ensuring firearms save bullets and hit their target. With its lock and key progression, real-time combat, and screen-based maps, AitD is a 3D translation of action-adventures and The Legend of Zelda, the year after TLoZ’s influential A Link to the Past released. Though loose in its mechanical design, Alone in the Dark proved a brilliant template to re-imagine Sweet Home just four years later, and Resident Evil recognized its natural cinematic power.

Capcom’s action game experience grounded Alone in the Dark’s gameplay, tightening up the controls and animations to add precision and responsiveness to Resident Evil. Crucially, it mapped AitD’s interaction options onto individual controller buttons and uses X to confirm selections and circle to cancel, so Chris and Jill run with square, push movable objects by walking into them, and aim their equipped weapon with R1. Aiming better communicates character orientation, with outstretched arms and weapon barrel creating a straight line to follow to your enemy, which, when paired with tight blast profiles and enemy hurtboxes, makes accuracy that much more important for resource management. RE’s detailed pre-rendered backgrounds fill rooms with information, which characterizes Spencer Mansion as a place with a history and forces players to pay more attention for items, especially when usable ink ribbons means even saves are scarce. Resident Evil was a personal, physical game, great for investigating rooms or shootin’ zambies, a fitting, very solidly constructed successor to The Legend of Zelda, Sweet Home, and Alone in the Dark.

S.T.A.R.S. Field Training

It’s easy to run right past its lessons, but Resident Evil teaches many of its rules in the first few scenes, accompanied by a progression of smart audio elements. After leaving S.T.A.R.S. leader Albert Wesker and your colleague to investigate the gunshots coming from the west, the first in-engine cinematic moves your character across the large main hall, generating hollow footsteps that sound different on the carpet than the marble floor, and ends at the door on the far side, an animation of it creaking open acting as a loading screen between locations. The second area introduces you to Resident Evil’s primary antagonist: time.

It starts with a sense. The dining hall greets you with a grandfather clock, its beat filling the two-story high ceilings with dread. The rectangular room with long table in the center is a smart way of acclimating the player to the tank controls and multiple paths, giving them two lanes to practice running straight lines in tight places. The player’s steps are just similar enough to the clock’s ticking that they constantly remind you of its passage.

Where the main hall represented safety within the mysterious Spencer Mansion, the dining room is the first step to characterizing the building, as the large flat surfaces, columns, and fireplace make it feel orderly and mathematical, a structure serenaded by the clock’s precise ticking.

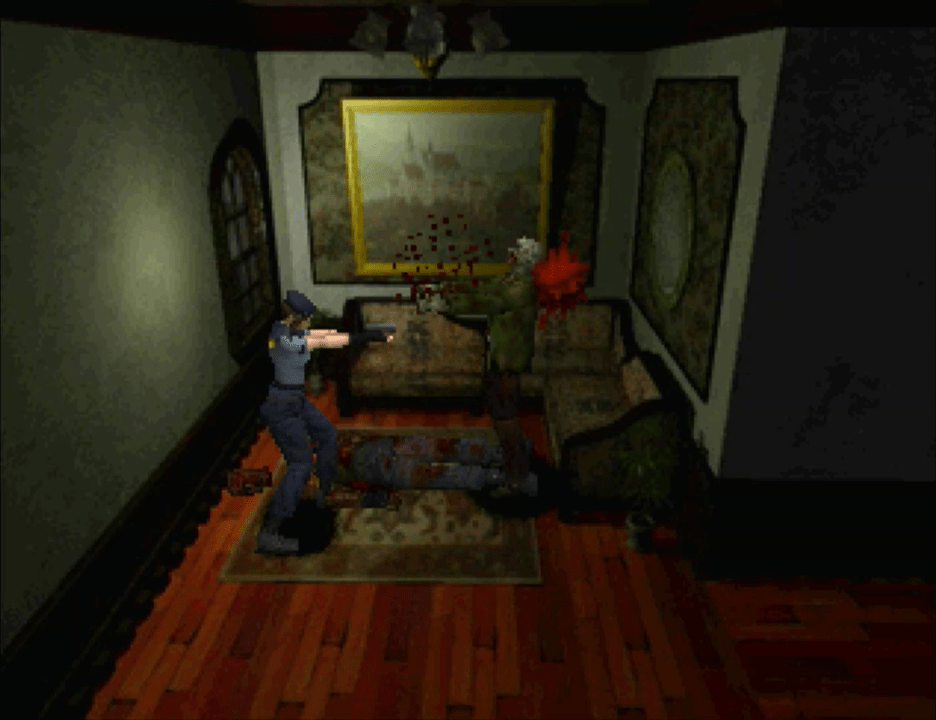

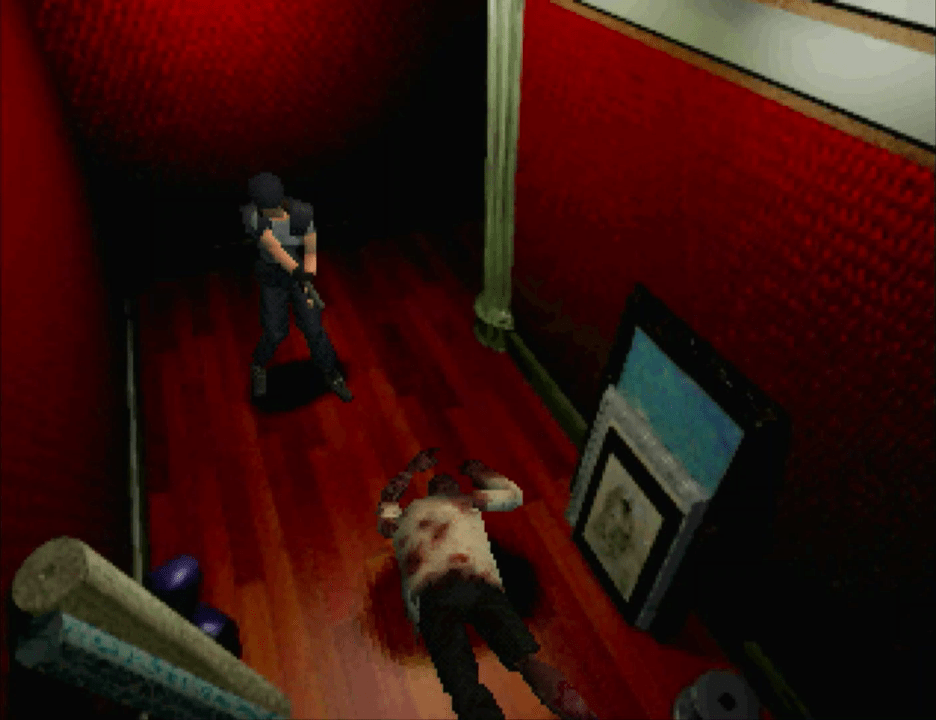

Compared to the main hall and dining rooms, framed to look open and large by the camera angles, the hallway off dining is tight and finds your character staring directly into a wall that extends to the left and right, the wet sounds of gnashing teeth just off screen. The reward for your sleuthing is the discovery of a pale, rotting zombie, whose biological decay contrasts the clean orderliness of the dining hall. As it stands from the mutilated corpse of Bravo member Kenneth and turns your way, the music rises to a shrieking pitch and ends with the sounds of footsteps if you run out of the room, the blast of gunshots if you stand your ground, or death rattles if you failed both.

Through RE’s functional audio design you’ve already come to understand that anything that moves produces sound, a mechanic that not only helps extend your senses past the limited camera angles but creates tension of knowing something is just off-screen. Unless that first zombie took you down, you’re routed back to the main hall where you find your team gone, replaced by an angelic chorus haunting the air above you. The soundtrack has kicked in and filled the mansion’s every room with mystery.

SOLVING PUZZLES WITH A BULLET

An adventure is filled with challenging tests with rewards that promote change. Though the route changes depending on if playing as Chris or Jill, by the time you’ve explored and shot your way through most of Spencer Mansion while solving block and logic puzzles, you followed a sequence of events that lands you at the gate to the mansion’s Grounds with the four crests to unlock it in your pocket. This sequence started by questioning where to go after returning to the empty main hall: do you return to the west side of the mansion or explore to the east? Choosing the east finds a blue room with statue holding a document, a step ladder against the wall– in one camera shot, you’re offered a puzzle with a goal, specifically a helpful map, and the means to reach it, but you must decode the process. This is RE’s puzzle logic simplified, but its found everywhere, starting with the combat.

Return to the first zombie for a second: with the combination of Kenneth’s motionless body and the way the zombie fell after you shot it, you realize that dead things lie on the ground. Because of that, you may disregard the zombie face down off the blue statue room, up until he buries his teeth in your leg as you walk by. A frantic head stomp finishes it off, blood pooling at his waist. Two lessons here: a zombie can be a trap and it ain’t dead ‘til it bleeds. The combat is full of puzzles determined by room shape, enemy placement, ammo inventory, and timing. Here’s a fun riddle: what’s the single most cost-effective way to kill a zombie? Aim your shotgun up when surrounded by a few and blow all their heads off with one shell, at the risk of shooting too late and being overrun.

Where fights are spatial and timing puzzles, environmental puzzles involve flipping switches or placing items into other objects and being rewarded with new items or locations. The damage taken shows how well you deal with the combat puzzle while the items collected shows your competency with the environmental puzzles, and being good at one type can compensate being bad at the another. These puzzles alternate into chains, and by designing several independent subchains that solve a main puzzle such as the crests unlocking the gate, the seemingly linear puzzle that is the gameplay has remarkable freedom.

Did you get your first crest by swapping family emblems or covering the poison gas vents? Plugging the jewel into the Tiger? The answer changes if you’re Chris or Jill, as the three keys she unlocks the mansion with are named after a suit of armor pieces while he finds those plus one engraved with a sword. Since their routing is different, their natural sequence for getting ammo and running into zombies is different. So decide if you’re gonna puzzle out a safe path getting ammo (and experience all the “You Died” Game Overs along the way) or dash the tight hallways evading claws (and see all the grizzly death animations when eaten). Safe rooms divide the map with item boxes and saving type writers, small sequences incrementally building out the progression. These quest chains, and their openness, teach you everything you need to know about the game, such as being patient and leaving that shotgun for later or the importance of friends watching your back. And once you understand the sequencing, it’s easier to break.

Of course, the game’s ultimate puzzle is the mystery of Spencer Mansion, solved lock by lock. Exploring reveals the Umbrella Employees stationed at the mansion, their diary entries and reports recording the rumors of secret experiments and loss of their humanity. Despite the voice-acted scenes, the times you fought and items you used are what really build out your tale, the story between the cutscenes. Jill is aided by S.T.A.R.S. dad Barry Burton while Chris finds Bravo rookie medic Rebecca Chambers, both searching the offices and dorms and fighting a giant venomous snake as the first boss, a unique most advanced combat puzzle, that marks the end of the longest Crest quest line.

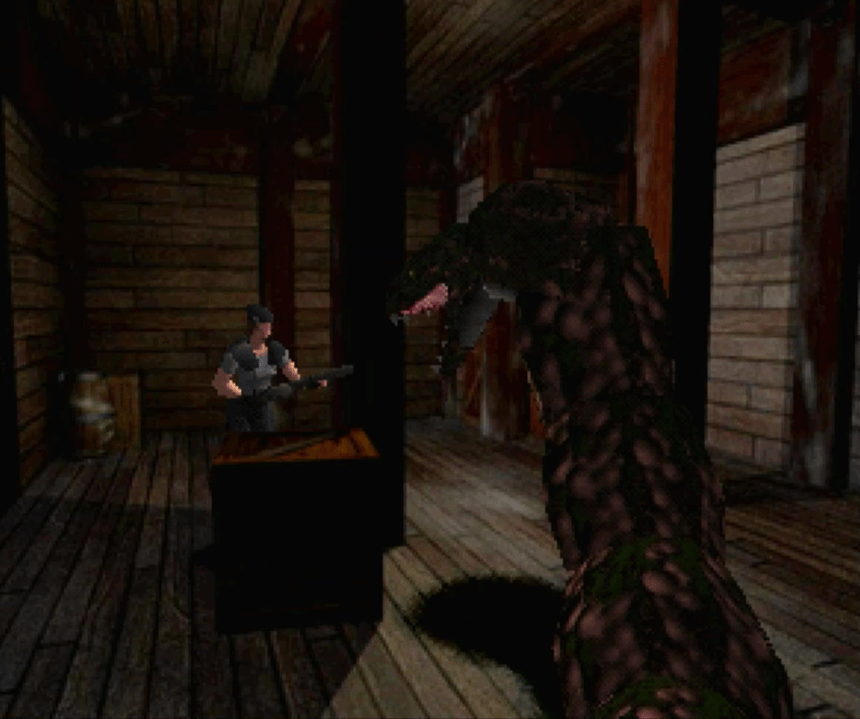

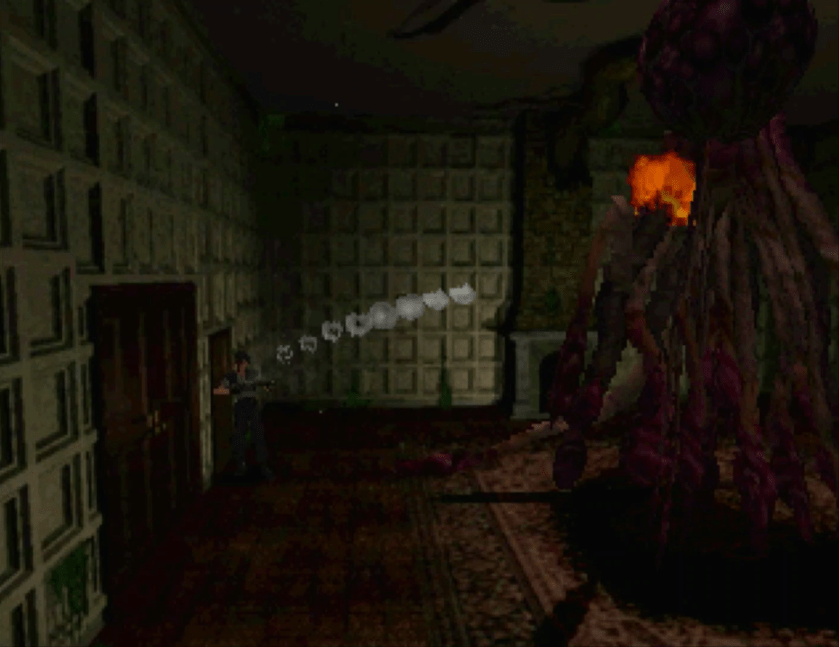

After a few hours in the mansion, the Guardhouse changes things up, past the Grounds path where spiders and a massive regenerating plant has taken residence. Deciphering the formula, you mix the Jolt V plant killer and chop the plant down, completing a contained quest line with boss that earns the last mansion key. Depending on how you’re solving the great puzzle that is survival, you may be hurting, you probably died, but if you get better, you may find that game saving ink ribbon you need for your current great run just right around the corner. And right when you think you have returned to the safety of the mansion’s already solved puzzle, Resident Evil throws a new twist into every area, a speedy green monster with razor-sharp claws- the aptly named “Hunter”.

Resident Evil’s many puzzles climax in a three way fight between you, the ultimate T-Virus creation, the Tyrant, and time, as you rush to escape Umbrella’s secret lab before it explodes. Depending on how well you solved the environmental puzzles, you could have found the MO Discs to rescue your teammates from S.T.A.R.S. traitor Wesker, and with how well you fought, could be coming with high health and full pockets. After firing a rocket into the Tyrant’s chest and riding off into the sunrise as Spencer Mansion blows, you’re given a grade based on time spent, items used, and number of saves. This is a challenge to completely unravel RE’s mysteries, and solve its puzzle faster. Considering how much of Shinji Mikami’s movie game had arcade genes in its adventure code, this grade is Resident Evil’s promise that it provides more than the chance to survive but the opportunity to thrive, in cinematic style.

DEVELOPER: Capcom

PLATFORM: PlayStation

1996

Dane Thomsen is the author of ZIGZAG, a sport-punk adventure in a world of electrifying mystery. With the voice of her people as her guide, Alex walks neon purple streets thrown into chaos, wielding the concussive force of her baseball bat the mighty ‘.357’ against the forces of evil. Print and kindle editions are available on Amazon. For sample chapters and to see his other works please check out his blog.