Metal Gear Solid’s story has been endlessly analyzed and deconstructed since it’s debut, a focus largely inspired by Hideo Kojima’s cinematic ambitions, but it’s gameplay has just as much to say. Though many of its lessons can be found in videogames generally, MGS’s narrative connects to its gameplay elements in subtle and profound ways through Metal Gear Solid, Metal Gear Solid Integral, and Metal Gear Solid 2: Sons of Liberty’s metaphors.

Together, these games form an important trilogy about data acquisition and scenario creation, showing the materials that build worlds, the mechanisms and systems that process it all, and how human behavior is directed and guided, even on societal levels. Their gameplay combines into the Solid Snake Simulation, the story of Players, Reality, and our Developers.

The Snake’s Blueprint: An Analysis Of Metal Gear Solid’s DNA

For the third time, legendary agent Solid Snake destroyed the walking tank Metal Gear deep behind enemy lines and saved the world from Armageddon, this time from his old unit FOX-HOUND led by his newly-revealed twin brother Liquid Snake. Until then, Metal Gear Solid had been an action-packed bonanza told through expertly produced cinematics that rivaled Hollywood blockbusters. And then the story pivoted at its climax. What had been a politically charged narrative about Cold War era terrorism and the threat of nuclear war changed into an examination on genetics, using the very technology and rendering techniques that brought the game to life to reinforce its deep and complex themes. With MGS, Hideo Kojima merged his narrative and gameplay abilities into a deep metaphor about biology, technology, and destiny.

In genetics, genotype and phenotype are two sides of the same conceptual coin, one informational and one material. In simple terms, a genotype is the information contained in a cell that instructs an organism to build in a specific way, while the end result, the physical part that manifests, is the phenotype. The genotype for black hair tints the melanin to color the physical hair itself, or its phenotype. This concept has similar parallels in many other areas- in architecture a set of blueprints is a building’s genotype; in baking, a recipe is a cake’s. Games work in a similar way, but their natures mean that the physical hardware has to produce its own digital building blocks.

Every videogame is a virtual machine that simulates its own contained reality and responds to player input. Comprised of if/then statements that do everything from load a map if you leave another, perform selected actions, and trigger events, a game’s programming code is the genotype and the product it displays on screen is the phenotype. The system’s hardware takes flat, two-dimensional information and produces an internal world. What the machine is capable of depends on the parts it’s built from including the strength of its processor, available memory, media format, and how well they all cooperate in tandem.

For his Directorial debut, Kojima created Metal Gear around hide-and-seek to accommodate for the MSX2’s technical limitations that could only display a few enemies on screen at once. Designed around self-contained maps of patrolling guards, the game’s overhead perspective provided the player with a comprehensive view of the land so they could puzzle out the best path to the next area. Metal Gear 2: Solid Snake solidified the concept a few years later, adding more advanced moves such as crawling to the player’s repertoire, which allowed more complex environments. Almost a decade after the first Metal Gear came out, so did a new console with enough memory to multiply its number of simultaneous operations, CD storage that could hold larger maps and high quality audio and video, and a processor capable of rendering 3D polygonal models. With the arrival of Sony’s PlayStation in 1995, Kojima returned to breathe new life into his stealth series, armed with new tools.

As genes build a three dimensional structure, polygons render shapes with height, weight, and depth, and can be sculpted into different shapes. Where sprite-based games use a sequence of individual pictures to show motion, polygonal models can be posed or moved on command. To make Snake a believable veteran agent, special attention was paid to all his actions right down to a proper firearm stance, a benefit of military adviser Motosado Mori’s consultation. Snake stands tall, he stays calm, he moves with purpose. You can see his personality in his actions. This adds so much.

The benefits of the polygonal world manifests only a few seconds after taking control of Snake. Press up to move and within a few steps you will run directly into a large tower and discover Metal Gear Solid’s primary new gameplay mechanic- the camera perspective changes when you press against vertical geometry, letting him peek out from cover. Over Snake’s left shoulder we see a white uniformed soldier, looking towards us, weapon in hand. This angle provides a new view without sacrificing Snake’s visibility. By the time we realize the soldier can’t see us behind the tower and isn’t going to attack, he turns and walks off. The corner view is functional gameplay presented cinematically, framed by a smart and reactive camera system. The angles became information-gathering mechanisms, providing the player with situational awareness while keeping Snake safely concealed in the shadows.

With the PlayStation’s advanced power, the nuclear disposal site Shadow Moses is rendered with as much character as the stealth agent sneaking through it. At a surface level, MGS is a more complex version of Pac-Man, complete with board and enemies, but it’s the fleshing out of dozens of details that brings the setting to life. Existing on a three-dimensional grid with height, width, and depth, the maps could have verticality to increase the real estate with which to place points of interest, with natural features like footprint-revealing snow and scurrying rats adding to its depth. At the same time, the patrolling enemies are given more personality thanks to the steamy puffs of breath and lines of recorded dialogue- add those to the already robust list of simple behaviors, and the enemies start to feel like actual people occupying an actual place. MGS simulates a logical world with consistent rules and observable behaviors, both important to the player’s success.

Since the camera becomes its own entity in a polygonal world, it can do more than be placed, it can be moved, be directed, all in real-time. Though it defaults to an objective angle in the ceiling, MGS can reposition to more subjective views around Snake. Shadow Moses’ industrial design also perfectly complements the camera mechanic. The right angles create corridors for Snake to peer while being consistent with the controller’s directional pad, which makes clinging to walls feel natural. And just as importantly, that camera gives the gameplay a uniquely stylish flair, bridging the divide between game and movie by meeting in the middle, and finally solidifying Kojima’s work into the interactive film experience that he had long pursued.

Hideo Kojima’s career until now had alternated between two completely different types of games: the action game and visual novel. While Metal Gear wasn’t the most action-heavy game, it had significantly more gameplay than the cinematically-rich sci-fi drama Snatcher; despite improving the narrative techniques in Metal Gear 2 it was the gameplay that developed new complexity, similar to the jump Policenauts made to become interactive cinema with its anime cutscenes and voice acted dialogue. All were packed with pop culture references and increasingly exhibited the creator’s willingness to push the boundaries of both videogames and movies. With the third Metal Gear game poised to finally apply the different skills he had been honing into a single work, Kojima remade the structural blueprint of the previous entry to create cinematic moments unseen in the medium before.

As polygonal models can be given animations for choreographed scenes, they become actors on a digital stage. It may seem like an obvious choice to render the cinematics in engine, after all, games had long used simply-shot scenes and pantomimed acting to push their stories, but its effects are still profound, and come alive with the right support. Where other cinematic games like Resident Evil and Final Fantasy 7 had inserted static Full Motion Video clips into their polygonal games, breaking their immersive cohesion, Metal Gear uses its camera system to tell a story by filming the characters inside the very diorama the player has been exploring. With full control of his narrative, Kojima’s shots move fluidly and cut dramatically, its characters emote with personality and interact believably. It’s an expertly crafted experience.

Though it’s taken many forms throughout the ages, the idea of the Game Master has existed for as long as games have. In its simplest shape is the referee, someone who enforces the game’s rules, but it has also evolved into the classic table top RPG concept of the dungeon master. The all-powerful DM establishes the setting, defines and enforces its rules, and creates whatever story they can imagine, leading the player past a series of challenges and enemies and responding to their actions. A videogame’s internal machine fills the same role, but invisibly guides the player by controlling the elements around them. In terms of MGS’s gameplay, the maps clockwork enemies, usable weapons and items, and events are all directed by the game’s programming. The game’s cinematics work in the same way, with the on-screen models moving based on their individual choreography, the camera panning and cutting dramatically on cue.

The attention to detail MGS gives to each of its separate parts comes together beautifully in the aggregate. It’s not that its setting is fit with steaming pipes and grungy walls, or that gunfire gets a punchy timbre and muzzle flare- it’s that all these can be produced at the same time. Look no further than the brawl against the Cyborg Ninja to see how the effects can layer on top of each other: fighting in the cramped office kicks up papers and wrecks desks, it breaks glass and tramples the shards underfoot, while the sound of gunfire and katana slashes split the air. It’s a thrilling fight.

This same creativity is exhibited throughout the narrative to keep its pace pumping. Though Metal Gear Solid is packed with interesting boss battles, from the bullet-bouncing duel against Revolver Ocelot to the tense showdowns at the end of Sniper Wolf’s scope, equal attention was paid to the many action set pieces, each as varied as they are harrowing. This is no more true than in the post-torture sequence, where Snake has successfully escaped imprisonment thanks to the clever application of a ketchup bottle – after tripping a security camera, Snake must fight his way to the satellite dish at the top of a tower, chucking stun grenades some ten flights up, only to repel down the side as he evades a barrage of bullets from a strafing Hind-D helicopter before finally taking it down with heat seeking Stinger missiles. These scenes are as stylish and well produced as any of the game’s cutscenes, just controlled by the player. All challenges portray Snake, and the real human holding the controller he’s tethered to, as a true hero that let’s nothing stand in their way.

For all his cinematic ambitions, Kojima always finds ways to extend his story’s themes outside his work, breaking the fourth wall between the game and player with precision and glee. Then he created Psycho Mantis. As the world’s most powerful psychic, Mantis’s telekinesis turns Snake’s young companion Meryl into his puppet, his mental strings moving the gun in her hand to her temple. In Metal Gear Solid’s structural metaphor, Psycho Mantis represents a brain, issuing orders to every Genome Soldier as if a part of a larger body. But when he moves the player’s controller with his mind and discovers they like Castlevania by reading their memory card, he isn’t so much trying to gloat to Snake as he is trying to make a connection to you- from one puppeteer to another.

Every third person game accepts this puppeteer claim by default, the controller connecting player to character, but Psycho Mantis hitches a ride up the string and interacts with you directly. Since Mantis can read Snake’s movements, his dodges tied to the player’s attack buttons, you must find a way to cut the thread linking mind to body by changing the controller from the first to the second port on the front of the console.

This is the game’s brain linking with yours. With this one character, Kojima is extrapolating the metaphor of the genes’ control over the body to a metatextual layer: if the genes dictate the physiological construction of all parts of the body, including the brain and how it functions, how much freedom do you have?

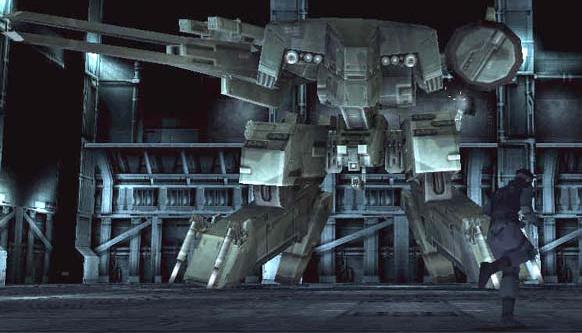

Snake, Mantis, Raven, Octopus- FOXHOUND’s naming convention has been integrated directly into the game’s subtext, representing a large swath of different forms an organism can take. But these are all types of living organisms that still exist, a contrast to Metal Gear Rex, named after one long wiped off the face of the Earth. Inspired by Japan’s big monster Kaiju films that emerged after World War II, Rex is every bit the nuclear war metaphor that Godzilla is, a rocket-launching dinosaur resurrected by Man. This is a battle between two machines, one organic and one artificial; Solid Snake fights an extinction level threat that could engulf all life.

But Rex was the product of human minds, a creation designed to claim power. Biology and technology are the two most powerful creative forces in the world, with organic beings creating new tools to overcome their physical limitations and reshape the world around them. And with the hardware that videogames operate on, creators are able to render new realities based on their imaginations, to let information become physical. They allow any experience to be simulated and any subject explored. By harnessing the power of videogames, Metal Gear Solid told a brilliant and action-packed story about life, technology, and the parts that build them.

Metal Gear Solid Integral: Upgrading The Solid Snake simulation

Lessons Learned

Metal Gear Solid’s post credit scene reveals that the nuclear-equipped Metal Gear Rex’s test data survived Solid Snake’s missiles, its log an invaluable learning experience for the developers. Similarly, snaking through the occupied Shadow Moses military base where Rex was developed required a lot of in-the-field training and dozens of hours, rations, and Game Overs, stats the game totals onscreen at its end. Of course, this is all created by a third set of data, the combined mechanics, systems, art, scripts, and modes that are the game. If the elements in Hideo Kojima’s classic thriller supports the theme of biological evolution, the very existence of its 1999 special edition, Metal Gear Solid Integral, tells us much about the new worlds that technological evolution is building for us, even on societal levels, as it upgrades its digital bootcamp to MGS version 1.2.

An important relationship exists between a design such as a videogame, its developer, and its user, with elements cut or added depending on how successfully they make the whole function. As people play a game, the developers see which parts work and which don’t and tweak future versions. Games provide tools to overcome the challenges in their worlds, and as a game’s gameplay builds over its series, the ability to experiment with its ideas becomes that much more important. MGS’s success drove demand for more missions as Snake, more places to sneak and shoot through, which required the devs at Konami Computer Entertainment Japan to add new tools to Metal Gear’s arsenal.

Hideo Kojima’s directorial style developed by zigzagging between action games and visual novels, first Metal Gear then Snatcher, Metal Gear 2: Solid Snake then Policenauts, taking every opportunity to experiment with new ideas and tech to tweak his two gameplay designs until he could finally merge them. The PlayStation’s polygonal camera was that opportunity, making the incremental change from 2D Metal Gear to 3D Metal Gear Solid possible.

Despite how important the camera system is to Solid’s design, its default top-down view and third-person shooting kept Kojima from capturing the intimate real-time shootouts of even Snatcher and Policenauts, especially after they got light gun support. While still primitive, MGSI’s ‘1P View Mode’ was good practice for a FPS, as double tapping triangle locks the POV from Snake’s eyes as he snuck past guards or shot them at range. The mode may lack precision aiming but it lets MGS and its boss fights be as thrilling and personal as Kojima’s other works. It marks an important step for future MGS gameplay.

As much as 1P View further connects the player and MGS’s world, putting you inside Shadow Moses, Integral’s true mission was to discover what that world was capable of producing by rearranging its cogs into 300 self-contained VR levels. Because of the relationship between developer, design, and user, this allows all to grow together: players teach developers how to better make games that train them to beat it, and for Metal Gear Solid, that means new ways to transform you into its legendary Metal Gear-destroying hero, Solid Snake.

The Test Environment

In addition to listing stats, that end-game report rewards your performance with a codename, but where MGS’s story portrayed Solid Snake as a super-agent that fit the moniker, your “Mouse” rank for dying a bunch and tripping too many alarms likely left some cognitive dissonance. The original set of 30 VR Missions was prep for the main game, distilling mechanics and systems down into simple challenges that taught the increasingly complex concepts needed in Shadow Moses. Integral‘s VR Missions Disc, sold separately outside Japan, was a chance test new scenarios while keeping the player focused on their exercises, all to mold a soldier that can efficiently complete any mission the first time.

Initially, the missions are simple maps with a specific weapon, but by adjusting rules, systems, and enemy properties, KCEJ could create hundreds of different tasks. Shadow Moses was itself a large layout of small maps connected together whose dynamic changes depending on the direction you enter, even if the enemy patterns remain the same. The game’s overall pacing is controlled by which maps get connected and what custom scenarios get inserted between them.

One of MGS‘s strengths was regularly switching between its standard stealth sections and mini-game setpieces, and VR Missions explored more ways to combine elements in unique ways. Instead of repelling down a building, fighting up a tower, and enduring torture, Integral has puzzles, variety levels, photoshoots, and adventure-game styled mysteries, all of which teach you how to interact with MGS and vice-versa. Integral even explores its place as a kaiju film, having you protect Meryl from the massive Genolla, a genetically modified Genome soldier whose individually targetable body parts would be used in future Metal Gear battles.

The VR Missions were the closest things MGS had to an arcade mode, right down to their scoreboard. Developers know that scoring systems motivate players to master a game, and VR Missions’ bite-sized levels means they can be run and rerun quickly for the hi-score, which provide more feedback loops for player improvement while Snake’s support crew showers them with praise. These small accomplishments help sustain player interest until they are trained into an efficient agent deserving a great codename.

As much as VR Missions helped iterate Metal Gear’s gameplay, what could happen inside its world, Integral secretly iterated on the identity outside it. From the OG, MGS reveled in being a videogame, of having branching story elements and fourth-wall breaking moments. But Integral took it’s meta level antics even further, setting up story elements that would soon make you re-evaluate what Metal Gear Solid’s machine was, especially where it came to the next player to take up the Snake codename.

Full Scale Deployment

To support Metal Gear Solid 2: Sons of Liberty’s meta commentary, its protagonist, Jack, revealed that he trained in VR Missions as Solid Snake, which directly and clearly re-contextualized MGS1. It asked you to accept that Integral‘s program existed within Metal Gear’s world as the Solid Snake Simulation which could create entire scenarios like the Shadow Moses Incident, and with it tacitly claimed that videogames are tools to program behavior. Despite the admission supporting MGS2’s larger analysis of media manipulation, it changed the perception of Metal Gear and videogames entirely, removing the barriers between developer, game design, and player, exploring how you are being revised and redesigned.

Social engineering is a multi-faceted field that studies manipulating people and controlling environments, and causing distractions, sabotaging surveillance, and swiping access cards to impersonate the owner fall under its auspices. But if a videogame provides tools to overcome its challenges, it is a social engineering machine whose gameplay, story, and presentation are designed to manipulate you into performing the behaviors it wants.

Metal Gear Solid‘s main story had already done a lot to keep you wanting to hone your skills, offering a gripping plot about heroism with multiple endings that instill the difference between accomplishing the mission and earning a happy ending. But score adds hefty gamification to that mission, stripping the valiant pretext from the violent actions until only the raw skills remain, a 180 degree turn from a narrative that grappled with the morality of killing. This very theme would be thrown back at the player in Sons of Liberty when talking about Jack’s detachment from his actions and their consequences.

The manipulation is even more interesting with the cyborg ninja missions, a fun hack and slash mode that lets you cut through waves of Genome soldiers. If the Solid Snake Simulation uploaded the ‘Snake’ persona onto Jack, then it uploaded Grey Fox’s too, a form of memetic determinism. But an important question remains: Did Solid Snake play the cyborg ninja missions in VR, particularly the mission to kill Solid Snake?

What do MGS2’s revelations say about MGS and Integral? If we are to believe that the Solid Snake Simulation was a secret project and Raiden its first trainee, could that mean that Metal Gear Solid never had you controlling Snake, it had you controlling Raiden as he ran Solid Snake through the Shadow Moses simulation? It certainly could be argued, and the problem with meta commentary that begs you to beLIEve so much wild stuff is that it doesn’t get to decide when you stop, up to reframing Metal Gear Solid from an artistic work about war to a game product that simulates an artistic work about war.

Sequels and new hardware offer the best chance for major gameplay revisions, and the PlayStation 2 gave Metal Gear Solid 2: Sons of Liberty a deeper first-person mode and location-based damage on top of new equipment and enemy A.I. MGS2‘s own Substance special edition offers more VR, but with media manipulation and social engineering so central to its story, it’s unique modes like Snake Tales and Casting Theater that truly support its theme, the latter of which swaps characters in cutscenes to continue engineering false records of the game’s events like MGS2‘s famous trailers. As the user and design becomes increasingly inseparable, Metal Gear would soon field test the larger system’s manipulative ability, and a chance to see the future that society’s developers have designed.

Metal Gear Solid 2 and Mass Producing Solid Snake

Metal Gear Solid 2: Sons of Liberty is celebrated for how it critiques social engineering, Hideo Kojima having crafted a theme that shows how controls built into the social fabric of a culture can shape an individual’s thoughts, beliefs, and actions. The story and game progression do an outstanding job subtly running players through a “real-world” simulation of the events of MGS1’s Shadow Moses incident as the rookie Raiden. It forced them to question whether their actions were truly their own or if they had been molded into a clone of Shadow Moses’ legendary hero Solid Snake, a test for the Solid Snake Simulation.

The theme is perfectly suited for the medium since it shares so many of the concepts as the behavior-based academic fields, including social engineering which uses tools to manipulate a situation. On a small scale, this means agents utilize spycraft, psychology, technology, and a host of other options to gain access to important locations and items. Exactly like Solid Snake does. But to truly own the idea that MGS2 creates Solid Snakes, its gameplay design must contain mechanisms that impart his skills to the players themselves.

It begs the question; does Sons of Liberty’s machine of interlocking mechanics and systems manufacture great soldiers? To answer that, we’ll need to examine its cogs.

To properly determine if the Solid Snake Simulation successfully produces Solid Snakes, the first thing that must be considered is what it means to be Solid Snake. Metal Gear Solid presented him as a specter whose considerable talents allow him to slip invisibly into any fortress and past the most hardened enemies. His character is concretely defined and the relative simplicity of the games design supports it.

Metal Gear Solid 2 is intertwined with Metal Gear Solid Integral, the special edition that combined the first game’s Shadow Moses story and an expanded set of VR Missions. MGS2 reveals that Raiden was trained in Integral’s virtual rooms, infiltrating digital environments effectively turning him into a hacker. MGS2 has him sneaking into the Big Shell to stop the rogue squad Dead Cell, essentially a team of Solid Snakes contracted to find and close system flaws so no other snake can slither in. These sorts of penetration tests happen all the time, pitting the red team attackers against the blue team defenders, swords against shields.

MGS2 expanded the series elements into a more complicated design and a much different dynamic. Your goal is still to get past guards patrolling set paths, but they are given greater sensory capacities, more realistic behaviors and stationed in a complex facility with multiple levels that create a wide variety of game scenarios.

Sneaking through an area unnoticed requires maneuvering the character outside the lines of sight of its guards and obstructing them with objects in the level. The industrial Big Shell is a geometric place ideally built for its fixed-but-dynamic camera perspectives and the four cardinal directions of the dualshock 2’s D-pad. Because walls, boxes and other fixtures are placed consistent with the buttons the player uses, they won’t find themselves struggling with basic positioning techniques.

The pursuit of harmonious stealth is about establishing a rhythm of action and observation, about finding the gaps in the angles with which to move, holes that get smaller and their timing more precise with every guard in the area. To widen the gap, options were implemented to disrupt guard’s patrols, from knocks to draw them away from their tracks to nudie books that stop them within them.

For the two team hide-and-seek gameplay to work in a model that has a universal ruleset and mutual vulnerabilities, the game has to properly communicate the player’s surroundings. The single most effective tool is the powerful soliton radar, which trivializes the game to the point where you’re playing Pac-Man in a corner of the screen, sins by not forcing you to develop as an agent. The rest make admirable attempts in its stead, offering the AP sensor that detects nearby enemies and the corner and first-person views, but the sheer number of discordant options requires you to regularly-and awkwardly- switch just to get a grip on the scene as it plays out. You’re given things to succeed, but not a working approximation of situational awareness. You learn much about a room’s unique rhythms through trial-and-error.

Think about what happens when you get spotted. The shrieking stinger and massive ‘!’ triggers your adrenaline and focuses your attention on the immediate threat so you can act. But as the guard retreats to safely radio in your location, he breaks his line of sight to you and gives you time to either hide or rush forward and engage them depending on your preferred playstyle.

Because Metal Gear’s competing forces create fluid situations of normal, cautious, and alert phases, the large toolset valiantly affords a wide spectrum of gameplay styles, from silent infiltrator to aggressive warrior. The flexibility of the gameplay means that it smoothly transitions to meet the flow of the game.

Having your location radioed in by a guard is met with a heavily-armed crew of foot soldiers. If you decide to stand and face them, you’ll be confronted with assault rifles and riot shields. If you hide, they will actively clear rooms and open lockers. Since enemies will infinitely pursue you, there are only two outcomes after you’ve been spotted: successfully hide long enough for the patrols to give up or die. Regardless, the punishment for being spotted is high and the off-screen opposition acts as an ever present reason to not make a mistake.

The small feedback loop will quickly teach you that the true warrior’s path isn’t sustainable for more than a few minutes, but that’s appropriate for a stealth mission. Unfortunately, the loop for infiltrators is much longer, its frustrations greater as you could easily spend an hour trying to get through one room without pulling out your guns, constantly being spotted, and be no closer to finding an ideal route. I’ve never figured how to deactivate the bomb in Strut F on European Extreme without using an item or alerting a guard.

Both ends of the gameplay spectrum steer the player back down the same path of least resistance. They lead to the suppressed M9 tranquilizer gun, a weapon so instrumental that you start the game with it. The tranq exists at the intersection of stealth and action, a tool to patch the way that neither is attainable in their pure form. You are so strongly incentivized to use the M9 that you’ll fall into a pattern of stopping at the entrance of a map, headshotting every guard in sight and quickly tiptoeing over their bodies before a team is dispatched to investigate.

By actively encouraging this behavior, it keeps Raiden from succeeding based on his innate talent while instilling in the player the idea that they’ve failed to live up to the image of Snake that’s been pushed over the series. This is the schism between Metal Gear Solid 2’s design: its mechanical construct clashes with the theme of its story. That’s the answer to our question; the Solid Snake Simulation that trained Raiden doesn’t produce great soldiers, the program not yet ready for full deployment.

The game’s narrative shows that Raiden couldn’t have accomplished his mission without Solid Snake’s repeated, direct intervention and that the only member of Dead Cell Raiden had definitely defeated on his own was Solidus at the game’s climax. In fact, he only succeeded after rejecting his conditioning and assuming his own, sword-wielding, identity. Ultimately, the Solid Snake Simulation code, housed within the massive Arsenal Gear facility below the Big Shell, only creates knockoffs of the original. But maybe that’s because of the differences between the digital world where Jack was trained and the real world he was deployed- there’s a compatibility problem.

Interestingly, the fact that Jack had been trained by an A.I. system and then sent to protect it radically transforms his role, making him more than a highly-skilled hacker. If Snake represented a biological virus in MGS, a vector for Foxdie to kill off Metal Gear Rex’s dev team, Raiden represents a computer’s anti-virus, digital white blood cells cleansing Arsenal Gear from the Dead Cell infection before Solidus and crew can destroy its body. In essence, the Solid Snake Simulation develops anti-Snake cybersecurity agents, making sure no one ever rises up against it again.

At its end, Sons of Liberty reveals its true manipulation system, the Selection for Societal Sanity, a social programming platform to mold all human behavior. Given that the Solid Snake Simulation’s prototype soldier was incomplete, the software was in need of bug fixes and revision. Does that mean other Metal Gear games could fit as additional VR scenarios to produce next-gen Raidens? Is Ghost Babel a mod to train basic behaviors in 2D? Does Ac!d teach strategy in low-intensity turn-based combat? Could MGS2: Substance’s VR missions be Solid Snake Simulation v2.0, able to remake Integral’s Shadow Moses into The Twin Snakes? Can’t know for sure, but we do know that Metal Gear’s social engineers would tweak and scale their design into a global machine to transform humanity, and that Jack’s ‘Raiden’ persona would be reborn to combat it.